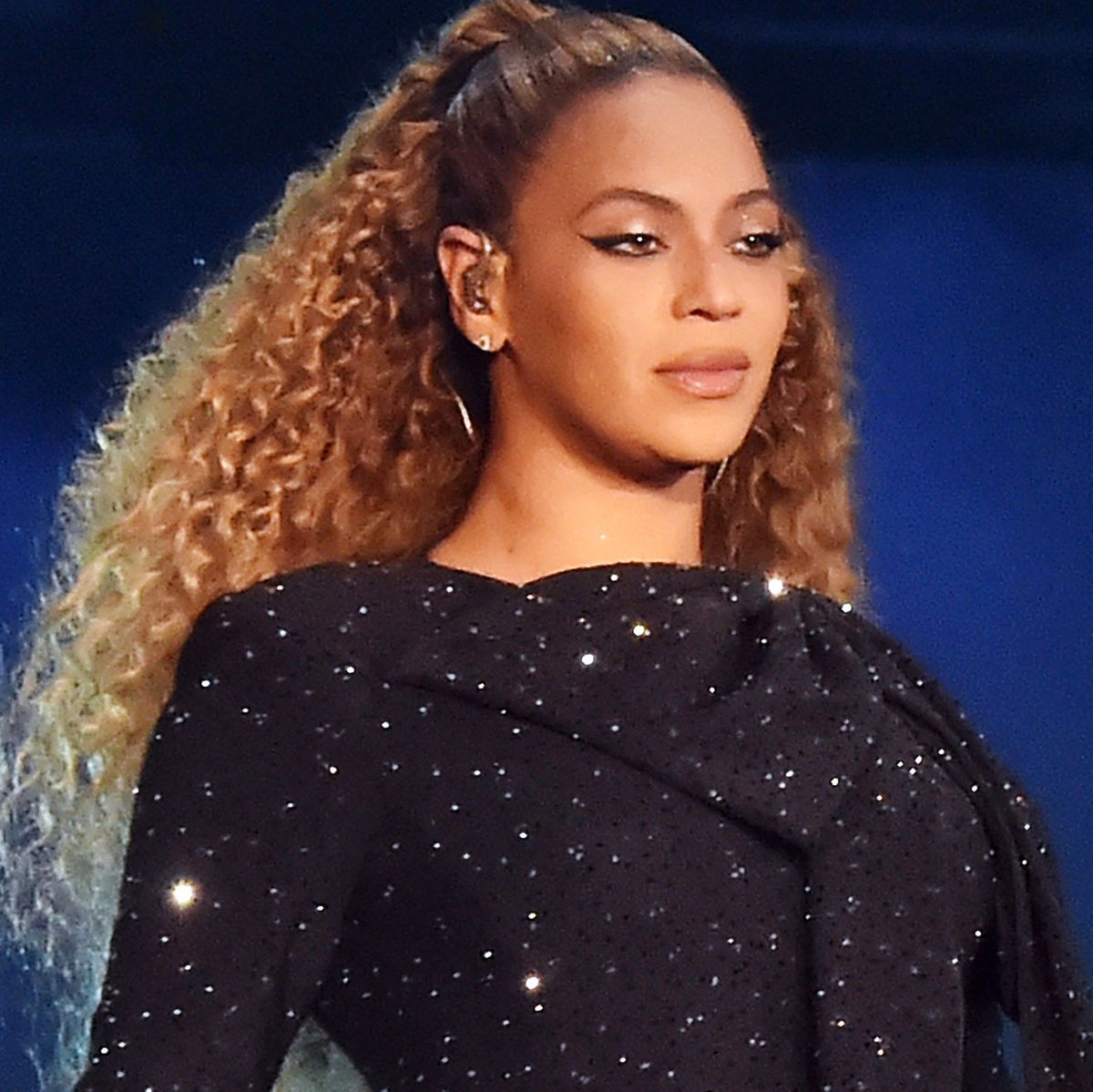

Via the album’s highly specific samples and features by artists like Jack White and James Blake, Lemonade proves Beyoncé to also be a new kind of post-genre pop star. The increasingly signature cadence, patois, and all-around attitude on Lemonade speaks to her status as the hip-hop pop star-but this being Bey, she doesn’t stop there. The run from “Hold Up” to “6 Inch” contains some of Beyoncé’s strongest work-ever, period-and a bit of that has to do with her clap-back prowess. If you have ears and love brilliant production and hooks that stick, you'll likely arrive at the same conclusion. If you’ve ever been cheated on by someone who thought you’d be too stupid or naive to notice, you will find the first half of Lemonade incredibly satisfying. Because she doesn’t scold, “Don’t you ever do that to me again”-she drags her very famous, seemingly powerful husband publicly, in the process giving the world a modern-day “Respect” in “Don’t Hurt Yourself.” On the “7/11”-style banger “Sorry,” she turns his side-chicks into memes, which will inevitably become “better call Becky with the good hair” sweatshirts that Beyoncé can sell for $60 a pop.

At first you might think that Bey is using the album to announce her divorce from Jay’s cheating ass. It’s not until the record's second half that you realize Lemonade has a happy ending. Lemonade is a film as well, yet the album itself feels like a movie. With its slate of accompanying videos, Lemonade is billed as Beyonce’s second "visual album." But here that voyeuristic feeling manifests while listening rather than viewing, given the high visibility of Bey and Jay. The songwriting is littered with scenes that seem positively cinematic, so it helps that you can imagine these characters living them: Beyoncé smelling another woman’s scent on Jay Z, her pacing their penthouse in the middle of the night before leaving a note and disappearing with Blue. So what we think we know about her marriage after listening is the result of Beyoncé wanting us to think that. Because nothing she does is an accident, let’s assume she understands that any song she puts her name on will be perceived as being about her own very public relationship. If the album is to be considered a document of some kind of truth, emotional or otherwise, then it seems Beyoncé was saving the juicy details for her own story. But Beyoncé’s “smile pretty and give no interviews” approach to public relations over the last couple of years, combined with “the elevator incident” and subsequent speculation about the state of their marriage, and followed by their public makeup (see: VMAs 2014, On the Run Tour), has suggested that something has changed, but that Beyoncé would prefer we not know the specifics. Over the course of their eight-year marriage and long courtship before that, Jay Z and Beyoncé’s private relationship seemed to play out in song, in concert, and of course, in the tabloids. Jay Z, on the other hand, is a rapper who used to rap brilliantly and sometimes still sounds good when he really tries, but his music has become secondary. With 2013’s Beyoncé, MJ-level talent met pop-perfectionism in a moment that defined album-cycle disruption moreover, it was a victory lap Bey took as pop feminism's reigning goddess.

Beyoncé and Jay Z are the most famous musical couple on the planet, and Beyoncé in particular is in a great place. The surrounding context is familiar to anyone who follows popular culture. On her sixth solo album, Beyoncé Knowles Carter starts rolling mid-scene: She’s just realized that her husband is cheating on her.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)